FIRST PRIZE

Gwyneth Talley (Assistant Professor, American University in Cairo): “Gunpowder Women”

These 4 photos are from a photo series meant to be viewed together from her fieldwork on Morocco’s minority women equestrians.

Through visual documentation, participation-observation, and interviews, she followed one of the few all-women tbourida (or fantasia) troupes in Morocco. The women stand out in contrast to the 20-30 men’s teams they compete against in local festivals throughout the summers in Morocco. Amal Ahamri’s team allowed her to accompany the women through the competitions and behind the scenes to ask what sets them apart from the men, but also how they are keeping this cultural heritage alive.

Getting Ready, 2016

Manar (left), Fatima (middle) and Bedia (right) in the process of donning their boots and sending last minute messages before mounting their horses.

Night Fire, 2016

The final charge down the field and fire the gunpowder rifles in perfect unison. This is a perfect scoring shot for the team.

Like Mother Like Daughter, 2016.

Amal celebrates a perfect shot with her daughter Lila (age 3) on top of her beloved horse Sharam Sheikh.

End Ride, 2016

Two young acolytes practice their riding skills at the end of a festival in hopes of riding in the next one.

SECOND PRIZE

Noha Fikry (PhD Student, University of Toronto): “Recipes for Relating: Home-rearing practices among women farmers in rural Egypt”

Careful selling

Poultry merchant selling chicks to a family in al-Daqahliyya governorate, Egypt. Poultry merchants wandering on their tricycles sell little chicks and poultry to women who rear them in their households for everyday nutritional sustenance. Photo taken during fieldwork & in the process of my interlocutors purchasing new chicks. Date: August 15, 2021.

A Palette of Rural Egypt

11-year old Hassan on a rooftop in al-Daqahliyya governorate, Egypt. Like many cities in rural and urban Egypt, agrarian fields are increasingly interrupted by 5 or 6-floor red brick buildings for larger and more families. Larger buildings denote status and wealth. Green, gray, and red form the current rural Egypt palette. Photo taken after a long sunset chat on rooftop rearing practices & rural-urban imaginaries with Hassan & his older sister. Date: August 15, 2021

THIRD PRIZE

Mary Elaine Hegland (Professor Emeritus, Santa Clara University): “Women and African Iranians in Ashura Rituals”

“Shemr” Goads Women Survivors of the Karbala Battle toward Syria, 13th of Muharram. (December 2, 1979), “Aliabad,” Shiraz, Iran.

Aliabad supporters of the Feb. 11 Iranian Revolution demonstrated their victory with a splendid Shii Muslim ritual. Commemorating the third day after the martyrdom of Imam Husein, they hired camels and horses, found costumes, and cowed relatives of the now defunct local Shah’s administrators and supporters. As usual, in the 1979 Aliabad commemoration, women did not join in the march of self-flagellants chanting couplets nor did they take any part in the Karbala passion procession. Most women stayed home but a few gathered to look on. “Shemr” (for Shii representing evil and injustice), dressed in red and on horseback whipped the female survivors, actually men, covered entirely in black and riding on camels. By acting in the pageant, these men demonstrated their loyalty to Imam Husein (representing courage, justice, religious power, preparedness for self-sacrifice to save Islam) and to the new Islamic Republic. However, representing a female may also have been problematic: one man shields his face.

Bushehr Women Singers Actors as the Karbala Battle Surviving Females, 13th of Muharram (Nov. 6, 2014), Bushehr, Iran.

Elsewhere, Shii Muslim men represented the captured women taken into captivity in Damascus. Including women in the Bushehr passion plays was likely influenced by the early history of African captives brought to the Port of Bushehr. The beautiful, high voices of these women, representing the women captives, soared above this street theater commemoration of the Karbala battle events. A unique form of self-flagellation to express grief for Imam Hussein’s martyrdom had developed in Bushehr, also quite likely influenced by early African cultural conveyors. Mary saw this rhythmic ritual, almost like a circle dance, called Bushehri, likely spread through Youtube, practiced by young women in Peshawar, Pakistan–until their elders put a stop to this daring innovation.

This photo catches the females representing the Karbala survivors marching toward Damascus. The Holy Zaynab (representing purity, loyalty, devotion, sacrifice for Islam, and female suffering and courage), sister of the martyred Imam Husein, leads. The female representing her was dressed in a billowing long gown in green, the emblematic color of Islam (in contrast to the red of the opposing forces). She holds a tiny stretcher on which lay the body of the smallest martyr, Ali Asghar, wrapped in green kafan (burial wrapping). Following her came another female figure in green and then other females in black, one holding an infant dressed in green. All of the females were covered completely, including long face coverings reaching down to the waist, representing the Karbala women’s and their own identities as virtuous Shii women living up to Muslim rules for women’s modesty.

The Most Renowned Female African Iranian Ritual Leader of Bushehr and Her Daughter and Apprentice, the month of Muharram (Nov. 2014).

Very fortunate to travel to Bushehr during the month of mourning in 2014, Mary was able to attend the mourning gathering (women only of course) led by this rozeh khun (martyrdom story reciter). Her daughter was learning from her and sometimes took the front to lead a chant or tell a story. Some African Iranian Shii women held their own rituals, and other rituals included both Iranian and African Iranian women. She asked if she could photograph her and her daughter and apprentice. The first photo showed them with solemn faces, the typical stance taken for the then rare photos among less affluent people. Mary asked if they could please smile. They were glad to comply, so I could represent them to my students and any other audiences as cheerful, affable, likeable people (in contrast to typically negative representations of Iranian in the US). A large billboard fastened to a wall pictured two famous men ritual leaders who had died recently, one of whom was an African Iranian.

The Renowned Female African Iranian Rozeh Khun Presiding at a Women’s Mourning Gathering in Bushehr, Iran, Nov. 2014.

For Shii Muslims, attending Muharram mourning commemorations for Imam Husein and his followers represented themselves as loyal Shii Muslims and followers of Imam Husein and his band. As the leader told the tragic stories, women wept and might slap their chests, representing their anguish and loyalty to the Holy Ones, thus deserving of their consideration. For one’s standing in the community and a closer connection to the saints, women should make visible their grief and compassion for the Karbala martyrs and prisoners. The woman on our upper left covers her face as she apparently weeps. On our upper right, a woman seems to be taking a break from representing a grieving and honoring Shii Muslim or is not interested in such a portrayal of herself to herself, the community or to the Shii saints.

Honoring and Beseeching Imam Husein and the Holy Ones, African Iranian Children Join in Lighting Votive Candles during Muharram. Bushehr, Nov 2014.

At a joint, night-time outdoor ritual gathering for women, several children light candles in hope of consideration from the Karbala saints. They also see themselves and are seen by others as Shii Muslims, honoring and loyal to Imam Husein, the other martyrs, and the female survivors of Karbala. Women covered in black veils sit chatting in the background. (Mourning rituals were also enjoyable social occasions.)

HONORABLE MENTIONS

1. Aamer Ibrahim (PhD Candidate, Columbia University): “Negotiating Sovereignty”

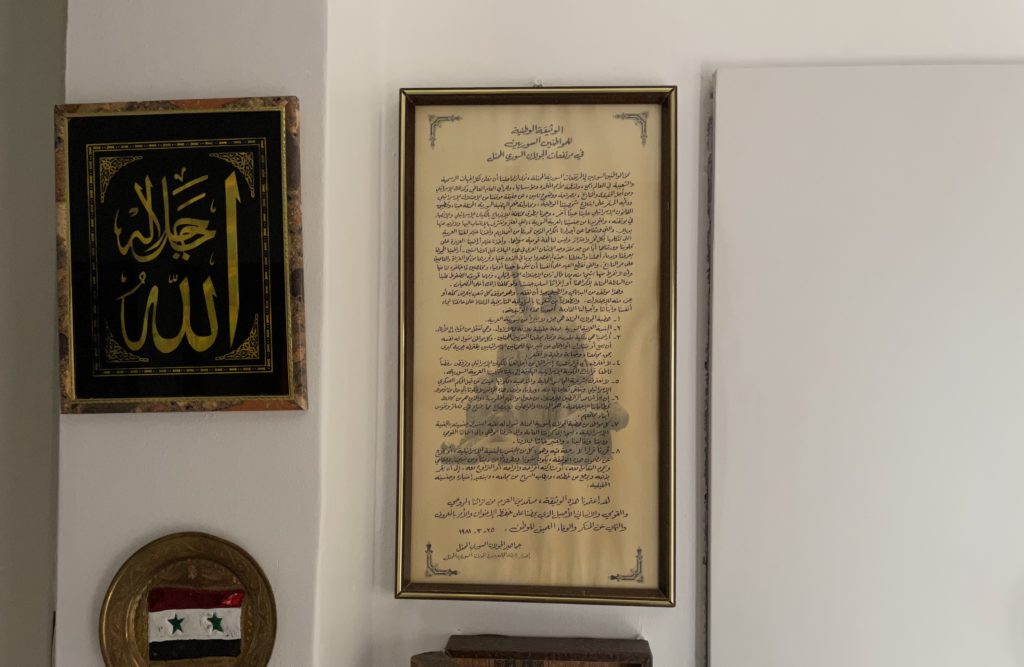

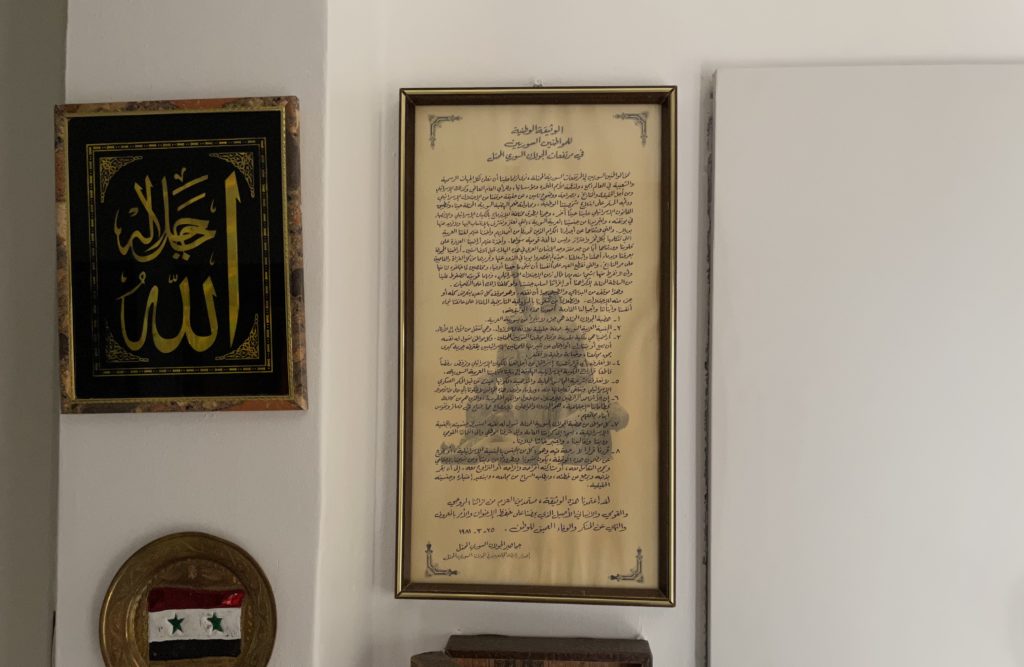

The National Document In 1981, the Israeli Knesset ratified the Golan Heights Law seeking to impose Israel’s sovereignty over the land and its people who fell under occupation in June of 1967. In response, the majority of the Golan’s remaining Syrian citizens issued a National Document calling for a refusal of Israeli citizenship. Today, and despite radical political changes, copies of this document are often framed and hung on entry walls of households in the Golan. Throughout Aamer’s fieldwork, he started taking pictures of these framed documents while paying attention to how and next to what other items they are displayed. (Date: Aug. 8th, 2021)

Cruel Representation At least since 2013, the Syrian residents of the Golan Heights have been strongly objecting an Israeli corporate’s endeavors of building 25 wind turbines on agricultural land adjacent to their villages, a project that gained momentum and received state and military support in 2015 when Israel signed the Paris Agreement according to which 10 percent of the country’s energy will be produced from renewable sources. The question of whether to have a legal representation before the Israeli judiciary on this issue or not has spurred serious conversations among the Syrian residents, especially about the consequences of recognizing such state institutions. Taken in February 2022, this picture is of a group of Druze sheikhs from the Golan waiting outside the courtroom while many other community members of men and women are inside attending the hearings (Date: Feb. 28th, 2022)

2. Dalia Ibraheem (Phd Student, Rutgers University):” The Poetics of Mahraganat Music in Egypt”

In this photo series, Dalia’s aim is to visually highlight multiple facets of mahraganat aesthetics in Egypt. Mahraganat music is an electronic dance music genre that started to gain popularity by the end of the first decade of the new millennium. Its artists are mostly urban poor youngmen and its sonic features include reliance on synthesizers along with a heavy percussion element. These photos do not stop at the figure of the artist or the individual’s aspects of the style, they also attempt to capture the wider DIY aesthetics of mahraganat making and circulation.

Posing for the ethnographer (2022)

Getting inside the studio; the thick carpeted sound-proofed, air-conditioned room with its dimmed lights, made this space even more removed from its outer context. The artist appears here in his element. With his hair carefully coiffed, the artist talked at length about his personal style and the choice of his clothes. He remarked “When I buy a t-shirt, I would buy all the copies I find at the store, so nobody in the neighborhood would be dressed like me.”

The Global Blackness of hairstyles (2022)

In this photo, Mr Jaxx (a hair stylist named after Michael Jackson), is box-braiding the hair of a young man in Cairo. He was telling me how mahraganat has revolutionized hairdos among youth from disparate social backgrounds. Before the popularization of this music, dreadlocks, braids and cornrows were not sought after hairstyles. As many mahraganat artists looked up to American hip-hoppers and copied their hairstyles, these trends started to gain popularity among youngmen in Egypt.

Nile Sensorium: Songs in circulation 2 (2019)

This is one of the motorboats stations in Cairo. Starting from sunset well into midnight, mahraganat music defines the soundscape of the Nile in Cairo as small motorboats start their nightly rides. Those boats constitute an affordable outing for non-affluent young people, especially couples. Cruising the river with their flashy fluorescent lights and dancy mahraganat songs, these motorboats appear as colorful fireflies in the darkness of the Nile.

Tuktuks: The Mediascape of mahraganat: Songs in Circulation 1 (2022)

Here, we see three autorickshaws (tuktuks) competing over who would pass first in an alley in one of Cairo’s underclass neighborhoods. The three vehicles are blasting out mahraganat songs. In fact, mahraganat is widely known as ‘the music of the tuktuks,’ as those vehicles acted as a medium for this music when state’s radio and television turned their back to mahraganat.